What is it about Albanian women?

There’s something else to them. Everywhere you go in Tirana, you are bound to run into beautiful, powerful creatures roaming the streets and filling its every cafe and byrektore. They strut the boulevards and alleyways of Tirana like goddesses, reincarnations of former princesses.

Albanian women are dynamic and fiery. Albanian culture is, in general, blunter and more direct than American culture. People here speak their minds and hide their emotions a lot less than Westerners, and Albanian women in particular are quite comfortable expressing themselves and their femininity with exceptional power and grace.

I think it all comes back to their roots. The myths of the past still inform today’s modern Albanian culture - sometimes for the better, sometimes for the worse.

What does Albanian mythology have to do with the modern Albanian woman, you may ask?

Anyone familiar with the legends of this tiny country knows that women play a central, sacrificial role in its mythical foundations. Oftentimes, women step up to the plate where men drop the ball.

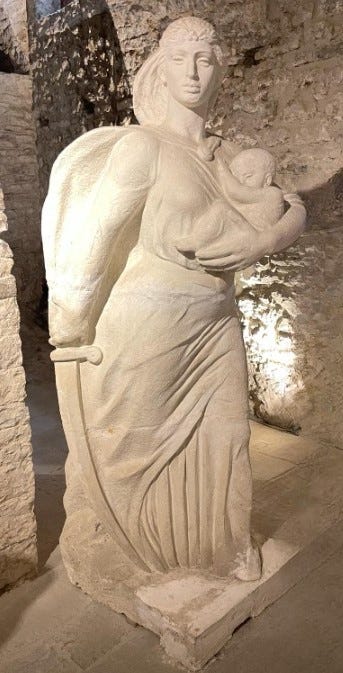

One of the most famous stories exemplifying this ethos is that of Rozafa, a selfless wife who sacrifices herself to save the crumbling walls of the Castle of Shkodër from falling down every night.

Rozafa’s husband is one of three brothers who attempt to build the castle’s walls. But, to their dismay, the walls fall apart every night, leaving the brothers defenseless against the elements and possible invaders.

The brothers are frustrated, if not heartbroken, and have no idea how to get around the problem until, one day, an old shepherd brings his flock through their ruins. Seeing their distraught expressions, he asks them what’s wrong. When the brothers tell them of their unfortunate architectural disasters, he responds with an enigmatic proposal: sacrifice one of your wives, and your walls will stay upright and strong.

The brothers fret about what to do, and eventually decide to give one of their wives up for the sake of the castle’s construction. But who to pick? The three agree that whichever wife came out first the next day to bring her husband lunch will be the one.

While the youngest brother keeps his word and didn't tell his wife about the arrangement, the other two tell their wives everything that night.

Maybe this is a story about the naivete that youth engenders. Maybe it’s a misogynistic way of putting women down - not only does the wife have to bring her husband the proverbial sandwich, but she gets nailed for it by being sacrificed in a castle wall, too!

When the youngest man’s wife comes out the next day to give him his lunch, he cries out in pain, explaining the agreement that the brothers had come up with.

But Rozafa doesn’t bat an eyelid. She gladly accepts her fate - on one condition.

“Let me be entombed with one breast outside the walls, so that our youngest son, who is still an infant, can nurse until he is strong enough to sustain himself.”

Does Rozafa complain about the patriarchal structure that demeaned and ultimately sacrificed her without her consent? Does she retort that it’s her husband who should be sacrificed in the walls of the castle?

No. She gladly accepts her fate - there’s a hint of joy in how the story is told. She steps up to the plate where the three men fail. She takes on a masculine role - she is the very glue keeping the walls up, getting the messy job of constructing a literal castle done where the men fail.

It’s this vein of storytelling that informs gender relations in Albania today. Women here are not entitled, nor do they complain about their lot - even though they have plenty to complain about. Salaries are low, the dating pool is increasingly smaller and smaller with each passing year, and most women have to both work and perform domestic duties, donning multiple hats.

(In a previous Substack post, I wrote a bit about how Communism actually brought about this interesting dynamic. Check it out below.)

How Does Communism Continue to Affect Albania Today? Part II

Last week, I published a piece about the lingering effects of communism on Albanian society (I recommend reading that post first! This one can be understood on its own, but the previous context will make reading this one a bit easier). I got mixed reactions from readers. Some people really enjoyed what I had shared, but two of my closest confidantes in A…

Many Albanian myths prominently feature this theme. The woman is more of a man than the men in these stories: when Princess Argjiro of Gjirokastër is surrounded by Turkish soldiers who have overrun the citadel’s walls, she refuses to fall captive. A plaque in the museum today commemorates the spot where she valiantly threw herself off the ramparts, child tucked into her breast; legend has it that her body was never recovered.

Self-sacrifice and duty comes easily to Albanian women. It gives them the license to be forceful and passionate.

Women here seem to be more in-tune with their spiritual sides, something they have perhaps inherited from their mythical progenitors.

It almost doesn’t matter whether or not Rozafa and Princess Argjiro ever existed; the fact that Albanians tell legends about these powerful, fearless women means that they valued the traits which the women certainly bequeathed their progeny.

My Albanian-Canadian friend and spiritual mentor Lueda Alia recently put it this way: “I don’t know why, but the women here are simply more evolved. There’s this wide gap between men and women in Albania; the women are just on another level.”

Maybe the women have simply been doing the heavy lifting in this tiny corner of the Balkans, and today, are reaping the rewards. How else to explain that so many of today’s pop-chart-toppers are Albanian women? Where would the world be without Dua Lipa? Rita Ora? Bebe Rexha? Ava Max? You can’t walk into a single cafe or mall (even in the West) without hearing an Albanian woman belting out a banger.

We’ll never know. Some claim it’s their exceptional beauty and ethnically-ambiguous features that make Albanian women perfect for the mass-marketing that comes with creating pop music.

But I think that the death of the Hoxha regime and the opening-up of the country allowed Albanian women to show the world who they really are.

Time magazine recently showcased Dua Lipa on its cover as one of the year’s most influential people. On social media, a post made the rounds contrasting the beautiful pop diva with the stirring image of a very different Time cover featuring a Kosovar Albanian woman, child held to her breast, fleeing from the Kosovo-Serbia war in April, 1999.

Almost exactly 25 years separate the two covers.

Times may have changed, but the magical Albanian women on their covers remain the same.