Why Do Communists Make Such Good Art?

How I Fell in Love with Albanian Socialist Realism and Why You Should Too

I have a confession to make.

I love Communist art.

For those not familiar with the country’s dark past, Albania suffered under a suffocating Communist regime that set up a massive secret police unit that spied on everyday citizens. It cut off access to the outside world and banned Western media. Criticism of the dictator, Enver Hoxha, or deviation from Communist orthodoxy, could land dissidents in jail and spell trouble for family members.

(Curious about the modern-day legacy of Communism in Albania? I wrote two posts on the topic.)

It wasn’t the brightest period of Albanian history.

But it sure did produce some great art.

What is Socialist Realism?

The birth of Socialist Realism can be traced back to the Soviet Union in the 1930’s. Similar to the ethos of the preceding Realism movement, Socialist Realism demanded that artists depict everyday people going about their lives and activities. Scenes such as churning butter, tending farm animals or working at construction sites could figure prominently in a Realism painting.

Where the two movements part ways is the perspective each lends to the subject matter. Realism demanded artists unveil the full palette of human expression in art and add as little interpretation as possible to their work. So, a Realism painting of a woman at a party may very well depict her boredom at the uninteresting chatter of a suitor, or the wild giddiness of a child leaving the classroom at the end of school.

Socialist Realism, on the other hand, was an explicitly political art form that preached subservience to the Marxist revolution and glorification of the struggle of the proletariat against the bourgeois.

That farmhand milking a cow? He is a valiant hero supporting the motherland in her struggle against capitalist imperial usurpers.

The mother mending a torn dress? She is sewing the very fabric of a united worker’s union against the exploitative evil of the West.

Albania adopted this art form as Hoxha came to power in the 40’s. He knew that art could serve as powerful propaganda and sought to influence the masses with the formation of Kinostudio, Albania’s sole film production studio in charge of all national media.

(Today in Tirana, you can visit one of my favorite bars/cafes adorned with movie posters, KINO, named after this film production studio. It’s across the street from Hoxha’s former residence.)

What’s So Special About This Art Form?

You would think that art produced under the watchful eye of a totalitarian communist regime would suck, but Albania’s Socialist Realism has produced some of my favorite works.

(Disclaimer: I am not an art junkie or critic, so if my reflections on Albanian art strike you as churlish or amateur, it’s probably because they are.)

There’s something fierce and inspiring about the paintings.

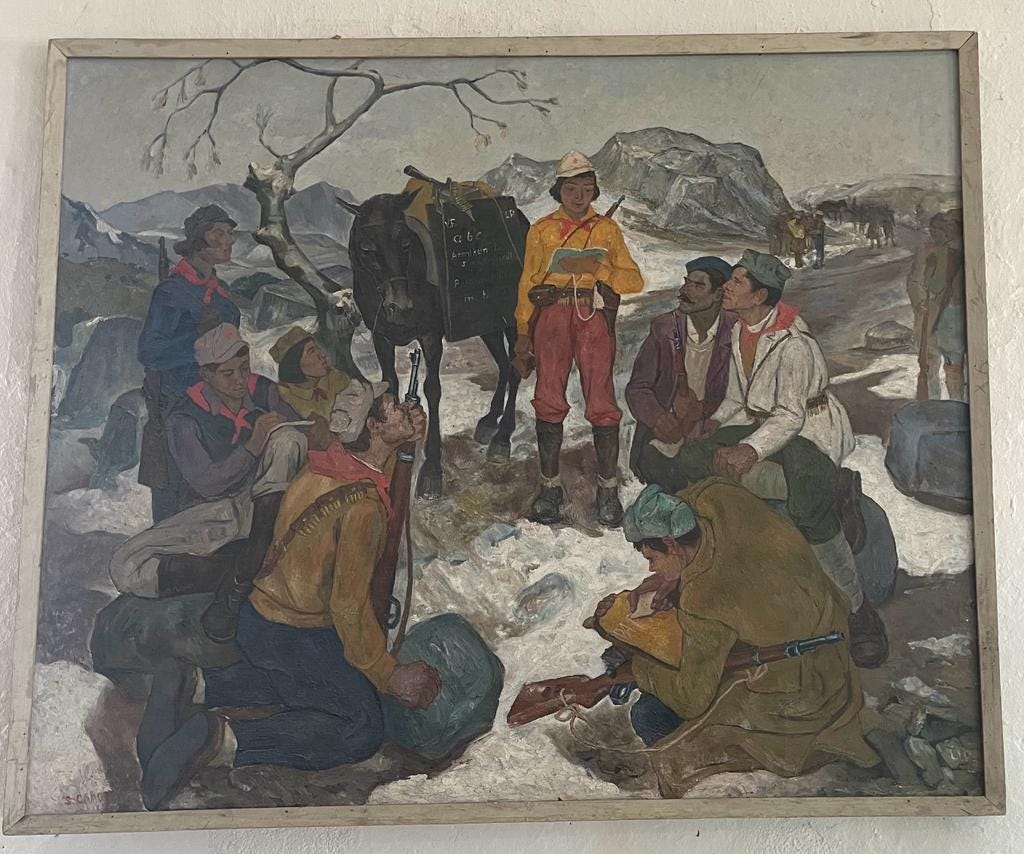

I first stumbled across the distinct art form at Gjirokastër’s Muzeu i Armëve, Museum of Armaments, a must-see for anyone interested in learning about the history of the country. (This museum and castle are the best in Albania.)

The top floor of the Gjirokastër museum houses the weapons which partisan fighters used in their fight against the Italian Fascists and Nazis over the course of the twentieth century, along with an inspiring array of paintings depicting their battles against the foreign interlopers.

The entrance to the museum contains a beautiful Socialist Realism-styled statue of Princess Argjiro, an Albanian princess after whom Gjirokastër is allegedly named. Princess Argjiro refused to surrender to the invading Ottomans who stormed her castle; instead, she threw herself off the castle ramparts, baby in hand.

Legend says their bodies were never recovered.

The artwork that adorns the halls of this museum is powerful. It tells of a people resisting foreign occupation with all their might.

Maybe I’ve just bought wholesale into the propaganda - but each one of the paintings in this museum speaks to a people dedicated to the liberation of their homeland from foreign powers that have no business being there. The proud, fierce partisans inspire feelings of patriotism and defiance in the onlooker as they hoist the Albanian flag and look out over the horizon at the rising sun. Rugged, youthful and powerful, these fighters are ready to fight ‘til the end.

They seem almost immortal, like they occupy a place above time and space: a group of fighters who cannot and will not die because the ideal for which they fight is righteous.

In another painting, male partisans in traditional garb proudly hold up the Albanian flag as they take aim at the foreign army below the cliffs. Their expressions are gruff, intent and focused: their gazes are fixated on the incoming armies below upon which they open fire, their passion for defending the country and pushing out the enemy on full display.

Albania’s Infamous Mosaic

Of course, every visitor to Albania will have probably observed Socialist Realism’s most famous artwork, “The Albanians,” the newly-restored, massive mosaic proudly adorning the National Historical Museum of Albania in Skanderbeg Square.

This gorgeous mural recounts the creation story of Albania and its unification in the face of multiple occupations and invasions.

As your eyes traipse across the mural, they are treated to the sight of various soldiers, partisans, workers and intellectuals of different backgrounds uniting behind the centered woman.

Starting on the left-hand side, a proud Illyrian archer strings his bow and takes aim at incoming enemies, representing the ancient roots of the Albanians.

The man with the double-headed eagle shield to his right flanked by other warriors represents the unification of the disparate feudal families of Albania under the stewardship of Gjergj Kastrioti Skanderbeg (after whom the square is named) in the 15th century. Skenderbeg was the first to unite the Albanian tribes under the emblem of the double-breasted eagle against the invading Ottoman forces.

(Read the post below to learn more about Skanderbeg and the importance of the double-breasted eagle in the formation of Albanian identity.)

The Boy and the Eagle

Once upon a time, in the mountains of Northern Albania, there was a young boy. The youth was tall and strong. He grew up in a small village nestled among the majestic mountain peaks of the Valbona valley. When he wasn’t hunting game in the forest, the young boy helped shepherd the family’s goats through craggy mountain passes and practiced playing the

The fierce bayonet-armed partisans on the right-hand side of the mural represent the fighters who resisted the Fascist Italian and Nazi occupations of Albania in the twentieth century, which united Albanians of different cultural and economic backgrounds.

The centered, proud young woman leading all the figures forward into the glorious future holds a rifle in one hand, the other raised in a call to unite the different aspects of Albania’s history.

Traditional Albanian women used to wear one of three dresses (called xhubleta in Albanian, pronounced zhoo-bleh-tah), each representing a different life stage: the virgin who has not yet been betrothed, the young woman who has been betrothed or married, and the elderly woman past her child-bearing years.

The defiant young woman in the center of the mosaic represents Albania herself: she wears the first dress of a virgin who has not been promised to any man, for Albania belongs to no one! She is free.

Another notable political message the mural and other Socialist Realism pieces depict is radical gender equality, which the Communist Revolution sought to advance by integrating women into the education system and workforce. Whether it’s the bright young woman uniting all the men behind her, the traditionally-clad partisan fighter behind her or the pants-wearing partisan on the far-right, women figure prominently as equal contributors to the formation of a modern Albanian national identity.

How Dare You Enjoy Communist Art?

Many Albanians have a hard time discussing the dark era of Communism. My understanding is that they feel uncomfortable recounting the unspeakable horror of the totalitarian state under which they lived; many feel complicit at worst and bitter at best when recalling what the Communists did to them and their families.

A fascinating article I came across interviewed two regime artists who came out of the era with entirely different feelings about the art they produced: one who saw real value and beauty in the art he produced, the other pain and disgust at what he was compelled to create.

“It would be a mistake to look at the art made during the period as a representation of how Albania was. It was how Albania was supposed to be in the eyes of totalitarian communist doctrine. The reality was very different — and we were seeing all of it, those of us who worked at Kinostudio. As a painter, while you may have painted the villager working happily with a pickaxe, in reality he didn’t have any food to eat at home.”

I think we can make space for both perspectives.

The paintings depicted what the Communists wanted the viewer to see: a strong, propitious and prosperous Albania that successfully defied foreign interlopers and led its working class into a glorious and united future.

The propaganda is powerful, yet any student of history knows it to be completely false. The Albanians defeated the Nazis thanks to support from the capitalist West and Yugoslavia, and the economic ruin that Communism wrecked on the country makes modern-day North Korea look like paradise.

And yet the images evince feelings of patriotism, love and admiration. They give the viewer the sense of belonging to something noble, of witnessing humanity uniting around a message that rings true and pure in every heart: that humans ought to be free from oppression.

Plenty of modern political commentators, even right-wing ones, have expressed similar admiration for the art that far-left, totalitarian ideologies have produced.

"My house was literally covered with paintings, every square inch, virtually ceiling as well, paintings everywhere. Technically, they were very sophisticated. And there was a battle between the propaganda and the art going on in the canvas all the time…That was really fascinating. Because over time, as we move farther and farther away from the Soviet Union, the art won out over the propaganda."

-Jordan B. Peterson

Because even though its political manifestation delivered the opposite, Communist art can still be admired for what it is: an ode to humanity’s magnetic attraction to freedom from persecution.

Hi Harel

I love your interest in the artwork created during that dark time. You will find that many artists under oppressive regimes have created beautiful art. (check out Hungary and Poland). This is what artists do.

I take strong exception to your title though. Good art is made by good artists... and in all likelihood they were not in alignment with the fascist dictates of their patrons.