Once upon a time there were two brothers.

The first brother’s name was Qurku. He was a handsome, tall young man with dark, thick hair and fair skin. He was always working his family’s farm, plowing the field, chopping firewood and faithfully herding the family’s sheep and goats. He smiled easily and took care of his younger brother and sister and parents, because he knew that family came first. And he loved his family.

The second brother was Kuku. Kuku was a squirrely and nervous kind of boy. He enjoyed plucking the strings of the çifteli Father had gifted him on his thirteenth birthday. He had learned to sing the ballads of the North to the soft plucking of the instrument’s double strings in the small hours of the morning before the rest of the family awoke. Kuku made up songs about the way the sunlight danced off the top of the grapevines in the vineyard as the sun set and the ancient oras, under his breath, when picking blackberries off their bushes.

And then there was Selma, a beautiful young girl with eyes the color of the Adriatic sea and skin like the snow that lay at the top of Mount Jezerca. She laughed easily and made everyone around her feel light and airy, like they were sipping a pleasant raki shot after a long day of toiling in the fields. Her voice was sweet and easy on the ears. Every boy in the village dreamed of taking her hand in marriage.

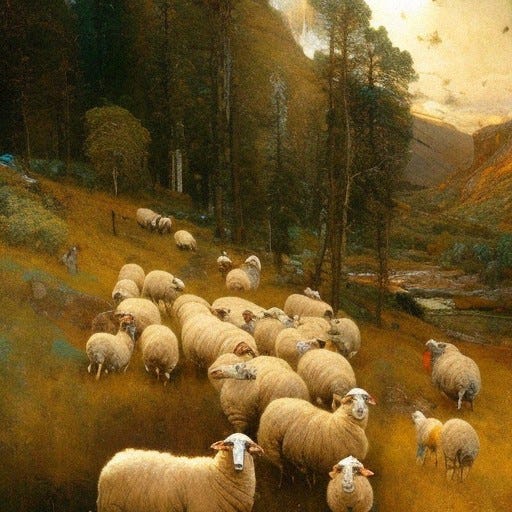

One day, Father sent his sons out to watch over the sheep. The family’s flock had grown large with the passing of years. Father had injured his foot many summers ago and spent his days in the garden of the farmhouse tending to its roots and vegetables, churning butter and maintaining the hearth.

“Be careful and quick, my sons; for the day is short and we must feed the sheep before winter’s harsh frost falls over the mountains.”

And so the sons set out one bright, cool morning with the sheep in tow.

“When Father speaks of winter, what does it make you think about?” Kuku asked his brother as they walked through the village outskirts towards a wide expanse of grass they knew lay on just the other side of the mountain pass.

“I think about how to keep the house warm and the frost out of our bones!” Qurku boomed. “Why do you ask so many questions, Kuku, instead of doing what must be done?”

“I think about how beautiful the snow will be on the top of the mountain, and the silence of the forest when all the animals have gone to sleep,” Kuku responded in a small voice.

The brothers trudged on in silence until they reached the great grass plain, whereupon they allowed the sheep to wander freely.

“Look at that beautiful bird!” Kuku said, pointing overhead to a magpie with magnificent blue streaks on its wings. The bird wove in and out among bare tree branches before settling on the top of a very tall tree.

“Yes, it’s beautiful, isn’t it,” Qurku responded airily, eyes focused on the sheep spreading out over the wide, rolling meadow.

Heavy storm clouds appeared out of the horizon. Kuku eyed them nervously.

“I think we should head back home,” he said. “It looks like a storm might fall over the mountain.”

“We can’t go home without feeding the sheep!” Qurku reproached his little brother. “Spend less time with your eyes on the horizon and more time scouting for kindling we can use to keep warm this winter, brother!”

“But the sky is about to unleash a flurry of hail and snow. I think we should return home.”

“Snow this early in the year? Impossible!” Qurku huffed. “You should care to the sheep rather than worry about the weather. Don’t you hear the bleating of the sheep getting lost in the forest?”

The conversation came to a lull. The far-off bleating of a single sheep came out of the forest.

“Go, collect the sheep before it gets lost in the undergrowth,” Qurku commanded his brother. “I will stay with the rest of the flock here.”

But Kuku searched and searched and searched among the boughs of the trees and found no sheep.

The younger of the brothers returned empty-handed with a nervous grin on his face.

“You didn’t find the sheep?”

“No, Qurku, I don’t think any sheep got lost in the forest!”

The brothers sat again to watch over the flock. Under his breath Kuku started to hum an ancient song. His index finger and thumb ached for the soothing reassurance of his çifteli strings.

“Shhh!”

“What? What is it?”

Again, from the direction of the forest came the undeniable sound of the bleating of a sheep.

“See!”

“Yes, I hear it too,” Kuku said. “Let me see where the sheep has gone.”

But the second time entering the forest was no more fruitful than the first. Try as he might, looking under every branch and parting every bush, Kuku found no sheep in the forest. He returned to Qurku once more with nothing to show.

Qurku stood up, a hot flash of anger coursing through his body.

“You are useless!”

Qurku struck his brother with the open palm of his hand.

“You are always singing your songs and talking about the weather instead of doing what must be done!”

“I am sorry, Qurku!”

But there was no appeasing the older brother. Qurku struck the young Kuku again on the side of the head and his brother fell backwards, his head striking a large stone before his body fell onto the soft grass.

And for a moment, the only sound that could be heard in the meadow was the soft clinging from the bell tied around the lead sheep’s neck as it industriously bit into the verdant grass of the field.

“Kuku,” Qurku said softly. He knelt down and shook his brother’s limp body.

But there was no response from the younger brother. The stone his head had struck glistened with the bright red stain of blood. Underneath the young boy’s head a pool of red liquid started to gather.

“Kuku, my brother, my blood!” Qurku screamed, shaking the spiritless body in his arms. “Kuku, wake up!”

Tears welled up in Qurku’s eyes and a terrible realization fell over the older brother.

“What have I done,” he muttered under his breath. He put an ear against Kuku’s chest and heard not a single heartbeat. He touched the young boy’s neck and felt no pulsating veins circulating blood through the young body.

“Kuku!” Qurku yelled to the heavens. “Kuku! Come back to me!”

But the body lay still; there was no bringing the boy back.

In his grief Qurku stood up and staggered towards the sheep. Through a thick haze of tears he pulled out the small dagger he kept on his belt at all times.

The blade glistened in the bright sunlight for just a moment before Qurku drove it deep into his own heart.

The second brother collapsed onto the grass, his blood flowing out from where the blade had been lodged deep in his flesh. The last thing he heard were the innocent cries of the sheep grazing in the pasture.

***

At first it was a light rain that fell over the mountains of the North. The villagers took no heed of the light drops of water as they continued to toil under the midday sun.

But soon the bright day turned ominously dark, and the raindrops became a steady torrent falling out of the sky inundating the mountainous ridges below.

It rained until nightfall. It was as if the sky were weeping over the death of the two brothers and would not be consoled until all the liquid it contained was spilled onto the earth below.

The limp bodies of the brothers were washed clean, their blood seeping into the soft grass and down the gullies of the mountain.

It was the next morning when a group of three traveling tribesmen from another village found the two bodies lying in the grass.

The men knew not whose bodies they had stumbled across but could not turn away from the sight of the corpses. Under a hot sun that gave no hint of the previous day’s downpour, the trio worked assiduously to dig two graves in which to lay the brothers.

And so within the span of a day, the sheep were lost and the brothers buried in the fertile soil of the pasture.

Father, Mother and Selma waited nervously at home for the brothers.

“Father, it has been almost two days at this point,” Selma said after pacing the interior of the house for what may have been the hundredth time that evening. “We must find Qurku and Kuku.”

“I fear the worst has already transpired,” the man said from his seat in front of the fire. His glassy eyes could hide nothing of his own dismay. “Something must have happened to your brothers. ”

Selma’s eyes welled up with tears.

“It cannot be!” she cried out. But already, the heaving and sobs racked the beautiful woman’s body. A body that knew all too well that the worst had indeed occurred.

And no matter what Father said, Selma’s broken heart accepted not a single pang of comfort. The distressed young woman flung the doors of the house open and screamed out into the chilly mountain air.

“Kuku! Qurku!”

But only a vague echo answered her calls, mocking the young woman.

Kuku, Qurku…Kuku, Qurku…

The young woman’s screams only grew louder and louder as she ran out onto the grass, feet bare. But she felt not a thing, for the only pain the woman could register was the loss of her brothers.

“Kuku! Qurku!”

And again, the mountains reverberated with a ghostly echo.

Kuku, Qurku…Kuku, Qurku…

“Zot i Madh,” Selma shouted at the heavens. “If you cannot let my brothers live, take my own life away. Allow me to find my gjak and be reunited with my brothers, oh, please!”

At the sound of her words, villagers had come out of their houses to see what the fuss was all about.

But they saw nothing. All that could be heard in the village that eerily bright morning were the echoes of the cuckoo bird circling overhead.

“Kuku! Qurku!” it warbled as it circled high above the dispersed houses of the village and the mountaintops. “Kuku! Qurku!”

***

Few people know that traditional Albanian culture is chock-full of unique myths, legends and magical creatures. Some of these creatures include oras, mystical fairy-like creatures that each human possesses (one good, one bad) who try to influence and protect their human.

I heard the legend of Kuku and Qurku and had to write it down. In the original telling of the legend there is no mention of parents; just two brothers shepherding their flock and a grieving sister. I have embellished the legend with details I hope give it vividness and relatability the lay reader may enjoy.

A very interesting finding I came across when researching cuckoo birds after learning about this legend was that they are what’s called a “brood parasite.” Many species of the cuckoo bird actually do not hatch and care for their own eggs; instead, they lay their eggs in other birds’ nests, coercing the other bird into caring for their young.

This fascinating (if not disturbing) dynamic that cuckoos exhibit made me wonder if it was part of what inspired Albanians to come up with this legend: a bird that leaves its eggs in another bird’s nest does make you think about a maternal figure grieving familial loss.

The sister circling the mountains, forever screeching and looking for her lost brothers, is a perfectly archetypical image from Albanian folklore. These stories tend to bear a few common themes, and this legend exemplifies two of them: explaining a curious natural phenomenon (the odd sound that the cuckoo bird makes) and a self-sacrificing woman. Perhaps out of a sense of admiration (or something more sinister), many Albanian legends focus on women turning into inanimate objects or animals to uphold an oath or save their families and villages; sometimes, the woman kills herself in pursuit of a higher value or goal.

I will share more of these legends in upcoming posts.