How I Stumbled Upon a Fascinating Albanian-Jewish Connection

An ancient Albanian pagan dictum helped me understand a story in Genesis better

“Europe? Isn’t Europe super anti-Semitic?”

This is the typical response I get when I tell Jewish friends from the United States that I live in Albania.

It’s a well-warranted response. There are parts of Europe where Jews don’t feel comfortable walking around with their kipot or tzitzit on display, or otherwise visibly identifying as Jewish.

I remember when I visited Paris over winter break in 2019 how the French-Israeli couple standing behind me in line at passport control in Charles de Gaulle gave me wide-eyed looks.

“Is everything okay?” I asked them in Hebrew.

“Yes,” the short, concerned-looking woman said to me in French-accented Hebrew. But she stared at my head, eyeing the skullcap that adorned it. “But you cannot walk around in France with the kippah on your head. You need to take it off.”

I remember when I went to Podgorica for one Shabbat, how one man stopped me on the main boulevard as I walked around the city in my crisply-pressed white dress shirt and black slacks. He looked at my kippah and then at me, straight in the eye, an experience that in any other country would have given me reason to panic and run the other way.

“Israel, very good country!” he yelled, extending a hand to shake mine. “You are from Israel? Very strong. Very good.”

It’s funny how much people here genuinely like Jews. There’s a very strange and heartwarming affinity that Albanians express towards the Chosen People.

A rabbi who used to live in Tirana told me he thought the two nations must be related.

“When the Torah describes how Abraham had children with concubines and sent them away eastward with some sort of gifts, I think that must have been the Ilyrians. Or some of the forefathers of the Albanians. Because it really doesn’t make sense, this connection Jews and Albanians seem to have.”

The rabbi told me that those gifts were spiritual - our forefather endowed all his children with a predisposition to connect with the spiritual side of things, even if we practice different religions.

Maybe it’s why we get along so well. Aside from how Israelis and Albanians seem to be pretty identical in many cultural aspects - loud, brash, unfiltered, warm and unabashedly family-oriented (maybe that’s just part of hailing from the Mediterranean?) - Judaism and Albanian culture share a lot of similar values.

One such similarity is hospitality. It’s a principle mandated by Albanians’ besa, or commitment to honor and keep one’s word.

Back when Albania was an undeveloped, wild country with no roads connecting major cities or villages, traveling from one village to the other - even if they were separated by just a few kilometers - could take days or weeks due to the highly mountainous nature of the country, particularly in the North.

The Kanun of Leke, the canonical text of Albania’s legal system and cultural ethos, dictated how strangers ought to be treated when they arrived in the village.

An ancient pagan belief codified in the Kanun relates that “[s]hpia eshte e zotit dhe e mikut.” The house belongs to God and the guest.

If a traveler were to appear on the homestead of an Albanian villager, it obligated the host to treat the guest better than his own family. The guest had to be clothed, fed and provided with resources so he could continue on his way.

The Kanun dictated a guest be treated with such high regard because of the ancient pagan belief that guests were divinely-sent creatures meant to test the hospitality of a prospective host.

Ancient Ilyrians saw the guest as a celestial creature sent from on high to test the host: if he were to make the traveler feel welcome and taken care of, the host and his family could experience a bountiful harvest and a fruitful year.

But turning away a guest? That would bring upon the household of an Albanian the most disgraceful and shameful fate.

One only a fool would tempt.

To this day, when you walk the streets of modern-day Tirana, far removed from the soaring alpine peaks of Theth, Valbona and the rest of the breathtaking Albanian Alps of the North, people will usher you into their homes with smiles and hearts full of love. They care about the foreigners streaming into their country and will go out of their way to help and guide you so that you don’t get lost or ripped off. It’s a genuinely heartwarming experience.

And don’t get me started with the villages. If a villager sees a foreigner trudging past their house, they will invariably pull you into their home and offer home-made rakki and walnuts and figs straight from their orchards.

Anyone who attended Jewish day school or grew up learning Biblical stories can start to see the parallels with Judaism’s commandment to perform hachansat orchim, hosting guests and wayfarers, a precept personified by the patriarch Abraham in Genesis.

In the seventeenth chapter of Genesis, Abraham receives the commandment to circumcise himself and all the males of his house, an order he immediately fulfills. God promises Abraham in return that his progeny will be as numerous as the stars of the sky for adherence to this commandment.

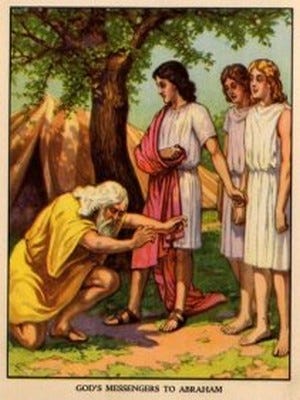

In the very next chapter, God appears to Abraham and tests him by sending three angels who appear to him as wayfarers on the hottest part of the day, traveling through the desert.

The third day, Judaism teaches, is the most painful healing period post-circumcision. Coupled with the fact that the Bible relates that the wayfarers were passing through at the hottest part of the day, Abraham’s insistence to bring the strangers into his tent is meant to impress upon the reader the immense importance of welcoming guests and wayfarers into one’s home, no matter the personal cost.

The three angels are brought into Abraham’s tent, wined and dined and given the opportunity to bathe their feet and refresh themselves.

Since he passed the test, the angels tell Abraham that the next year his wife would bear him his most precious son, the next of the Jewish forefathers, Isaac.

When I made the connection between the Albanian tradition of honoring guests warmly and Judaism’s ancient teachings around hacnasat orchim, the Albanian dictum that “[s]hpia eshte e zotit dhe e mikut” took on a new meaning. The Divine presenting itself to us in the form of a guest who may need assistance is the host’s opportunity to prove just how much he can help and extend himself.

How much can he dedicate himself to a total stranger and give someone outside his family the honor and resources you’d expect a poor farmer to hoard for himself in an attempt to survive the harsh elements of the Northern Albanian Alps?

It’s a form of hospitality I’ve had the pleasure of experiencing firsthand many times since coming to Albania.

One weekend, I went camping with three friends in the Karaburun peninsula, Albania’s only national maritime park. Night had fallen, and we were almost at the beach where we planned to camp the first night.

A blaze of light shone out of the bushes. A harsh, interrogatory voice yelled at us in thickly accented Albanian. All I could understand were the repeated calls of “Privat! Privat!”

I was with one Albanian and two other foreigners who spoke barely any Albanian. As the sole local among us tried to calm down the man with the headlight, I felt an icy hand of fear grip my heart, squeezing it tight.

We were tired and sweaty; it was dark and we had no idea what was going on or if we would be allowed to reach the beach to wash off the sweat and mosquito bites we had accumulated.

But the man came out of the bushes and recognized my Albanian friend: they were hiking buddies who had gone on many trips together. Suddenly, the tension in the air melted, and laughter took its place. The man led us to the beach, where he and two friends had been hunting for wild boar. They had been concerned that they might shoot us, the only other large animals walking around the wild bay at dark.

I gulped with relief that we hadn’t been shot. The man ushered us towards his fire and commenced to cook the fresh pork chops he had cut off the boar he and his comrades had just killed. We were offered a massive amount of fresh vegetables, meat, melon and rice by a near-complete stranger who wanted to make sure we had a proper dinner.

We had come to the campsite prepared to eat some canned tuna and packaged cereal for dinner; we were treated instead to freshly caught game and produce that we could have never carried on our own over the course of our three-day hiking trip.

The Albanian mentality around honoring guests and giving to those in need is always on display, and is one of the many reasons I feel safe and content living here. It’s funny how in the United States, we tend to view people in poorer countries as potentially “dangerous” or more prone to committing crimes out of financial desperation when, in reality, it’s those who have the least (or less) that tend to give the most.

The kindness of Albanians continues to inspire me every day. The connection that Albanians and Jews seem to share goes beyond recent history, tracing back to shared values around hospitality and the importance of welcoming foreigners and guests into one’s home as if they were Divinity itself.

Absolutely loved reading this! You might also want to look into how Albanians helped Jews during second word war.

Hi Harel: you might be interested in some of the pieces I'm writing about Albania. Loving your work! Allan